I still remember the moment I found that plastic bin like it was yesterday. My grandmother was throwing out my late grandfather’s old belongings, clearing out the clutter that filled her closet from a lifetime well spent. Old clothes, trinkets, antiques – all the stupid stuff a guy like me loved to mess around with. She brought out a plastic bin; one that you would pass by without a second thought every time you frequented the supermarket. My grandmother handed it to me and allowed me to look through it, to my delight. I sorted through old keychains, coin purses, long-expired hotel visas, and an inconspicuous pile of dusty passports. Alright, I thought. The usual: a passport from the 90s when my grandmother drove her family to El Salvador post-civil war. My uncle’s passport from that same period. Even though I had known these people my whole life, it still resonated with me to see their young (and in my uncle’s case, still acne-filled) faces. I felt like I was peering into a past held only in memories and forgotten blurry photographs.

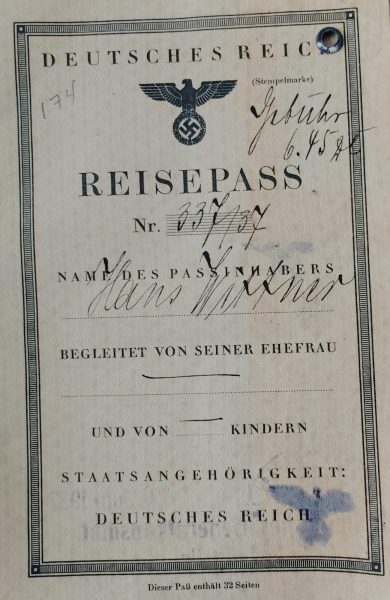

I dug further into the bin, pulling out more and more documentation she had stored. More passports, some designs now obsolete and foreign to me. My grandfather’s visa from El Salvador to the US – that was pretty cool. Some vintage half-dollars from the early 20th century – pretty neat. A Nazi passport.

Huh?

I blinked twice. No, those midnight binges of the History Channel hadn’t rotted my mind yet. In my hands, I held an authentic 1930s Third Reich Passport.

It was strange: my grandfather wasn’t Argentinian, neither was my grandmother. Why would my grandfather hold on to Nazi memorabilia? I inquired about it with my grandmother, and she gave a surprising answer. It wasn’t his, it was hers.

“That was my boss’s passport when he emigrated from Germany to Cuba.”

Why did my grandmother hold on to such artifacts? Was it something nefarious? Did she work for someone nefarious? My mind raced with these thoughts as I prodded her for answers.

“They were Jews. He fled Germany and moved to Cuba, while his wife moved from Poland a few years later.”

Well, that explained the Nazi passport, but not the reason she had it in her possession. And Cuba? Why was it in Los Angeles then?

Though It seemed strange to me at first, once I interviewed my Grandmother, she painted a clear picture. A vivid image of a couple divided; driven out by a murderous and hateful ideology, a reunion, skillful wile and business acumen, an American dream, and the tragedy of the early 20th century.

[This interview was conducted in Spanish and translated into English]

My grandmother had known the Wittner Family since she’d immigrated to the United States in the 1970s. Her mother – Mama Ofe, as I knew her – had immigrated earlier, and had found work in the Wittner cigar shop. Mama Ofe vouched for my grandmother and she ended up working for them.

“My family was close with them,” she said. “They treated us like their own children – we were like family.”

“Leti,[My late great-aunt], Heidi [My great aunt], and Mama Ofe [My great-grandmother]; all worked there,” My grandmother elaborated.

While working for the Wittner family – or rather, the Wittner Couple – my grandmother learned a wealth of information about their past, their family, and their reason for fleeing. According to her, Hans Wittner and Sarah Wittner were Europeans (obviously) and had known each other back in the old country. Hans Wittner’s relatives owned a “Bosque,” as she called it: They harvested firewood and owned a forest. Sarah Wittner was from Poland, and her family had her arranged to marry another fellow. She fell in love with Hans, but she was separated from him when he migrated to Cuba.

Then came Kristallnacht.

The Munich agreement.

Anschluss.

The concert of Europe was coming to a second, rapid death.

It was in this rise of evil that Hans called her to Cuba to help him with his ailment: His asthma.

She took the opportunity.

“…and so she went, on one of the last boats out of Europe,” My grandmother said. Many other European Jews were not so lucky. Much of the European Jewry was stuck in ports, hostile nations, and occupied zones, so they could not leave the coming persecution. The flames of war came, and the entire continent was shut off from the world.

“She never liked to talk about the Holocaust,” My grandmother said. “One time, Mrs. Wittner came to me and said ‘Listen to me, because I will never tell you this again,’ and so I did. Her entire family was gone – gassed in the chambers of the concentration camps.”

An entire generation of Jews perished in those camps; Six million souls were now forever gone in the evil death throes of a vile empire. Even so, the Wittners managed to find a living in pre-castro Cuba. The tropical country was known – and still is known – for its tobacco. The Wittners used their business knowledge to build a tobacco company from the ground up, and imported said product to the United States.

“Unfortunately for Mr. Wittner, he had asthma. The tropical air bothered him too much, so he moved to the United States with Mrs. Wittner,” my Grandmother said. Hans had fallen ill in Cuba many times due to his asthma and had many doctors advise him to leave the tropical paradise for less tropical ones.

That was lucky for them, as they managed to avoid the bloody Cuban revolution and its removal of ‘Bourgeois’ elements from their society. After the US embargo, the Wittners had to find another method of import, so they sourced from Mexico, Honduras, the Dominican Republic, and Nicaragua – all countries familiar to many students at MACES.

Mr. Wittner was the first to pass, dying in 1986 from a heart attack. Mrs. Wittner ended up moving to a retirement home from her Park La Brea home. There, my grandmother and my family became trustees – bringing cleaning supplies, groceries, and necessities to her new home until she died in the 1990s.

“When she passed, we all wept,” She recalled.

And so, there remain the last of Wittners, a family threatened to memetic extinction. Memories are threatened by the gears of time, and in this fleeting world, it should be up to the younger generation, such as us, to preserve what we can. I conclude this article with one final breath of a dying generation.

“In her final years, Mrs. Wittner began to confuse past and present. She said repeatedly that she wanted to go to Poland, and that she would take us there. We all nodded our heads, yes, but she herself said that there was nothing for her there. Everything was gone,” My grandmother reminisced. “She died before she could take us there.”

Gail Moore • Nov 17, 2024 at 1:48 pm

My step mother, Leora Moore, worked in the Wittners Cigar store for many years. She said they were very kind people. She often wondered whether Mrs. Wittner was still alive after she retired and moved to Texas. Thank you for sharing.